Introduction

The battery industry faces increasing demands for high-performance electric vehicles (EVs), low-carbon recycling processes, and other environmentally forward solutions. To address these demands, it is critical to optimize every step of the battery fabrication process, including early steps such as producing high-quality precursor cathode active material (pCAM).

Physical properties of pCAM have a significant impact on the corresponding battery’s cycle life, charge capacity, and charge/discharge rates. These parameters include particle size and distribution, particle morphology, crystal microstructure, and purity. A desktop scanning electron microscope (SEM) can be used to characterize these, ensuring the production of top quality pCAM for battery research and development.

What is pCAM?

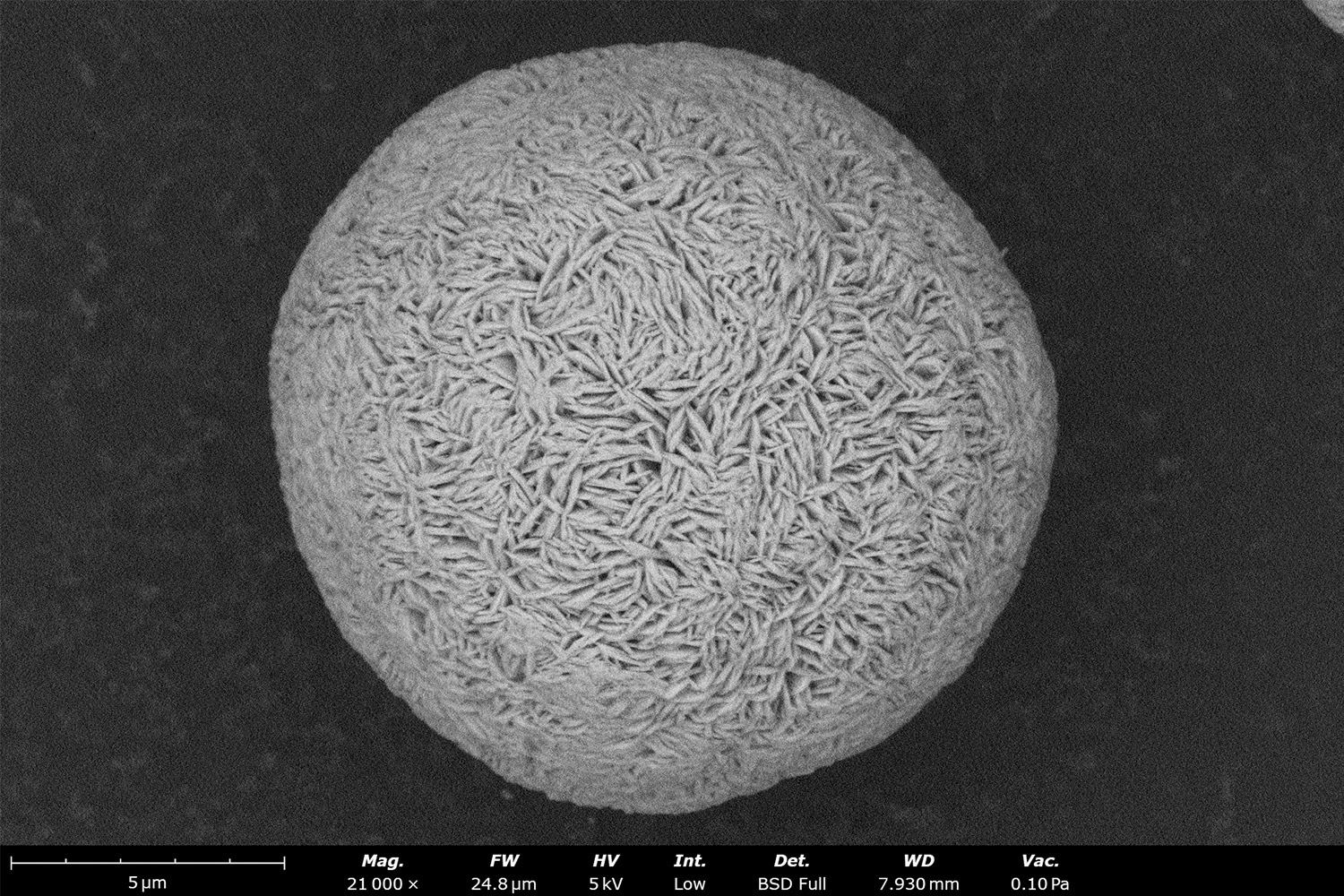

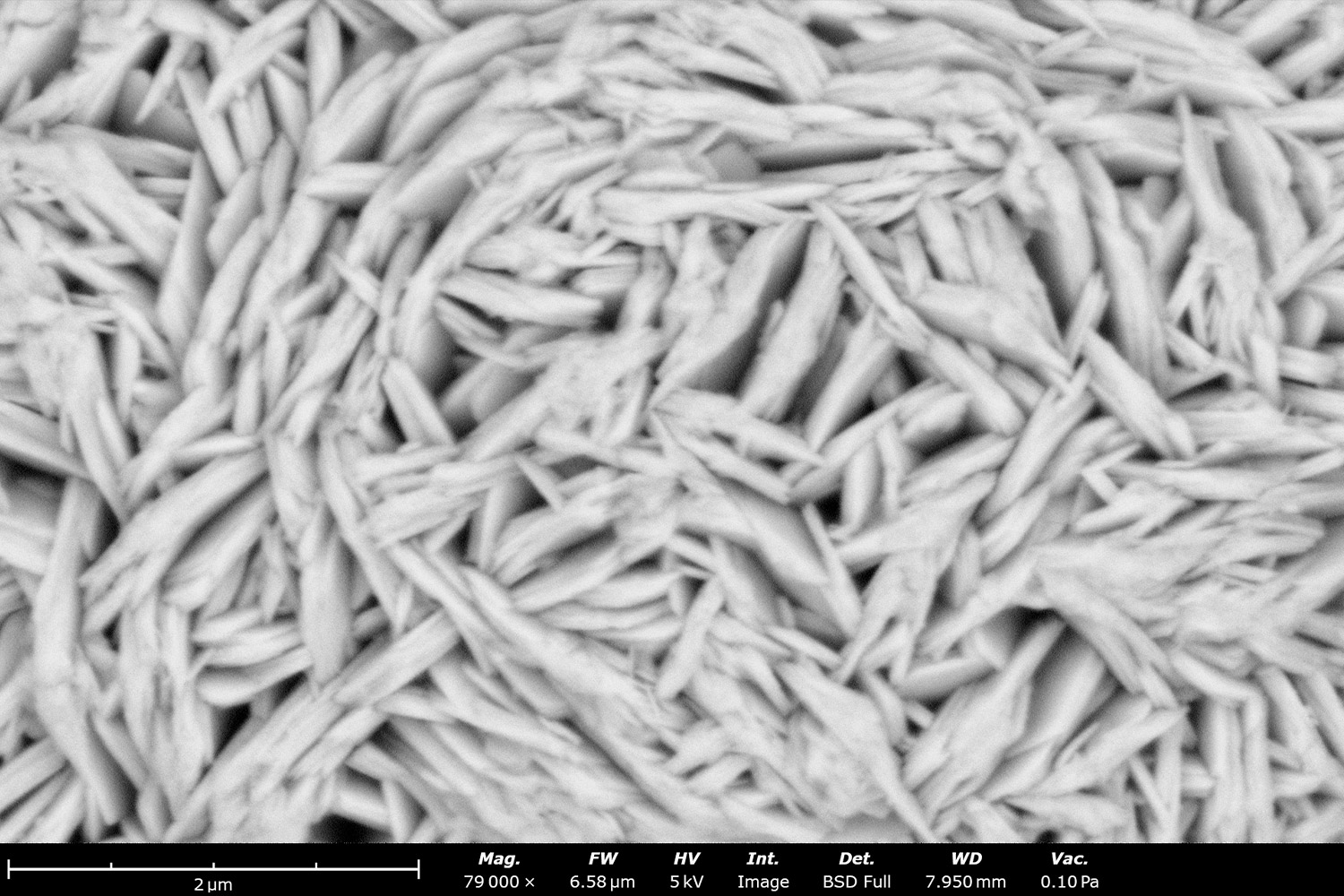

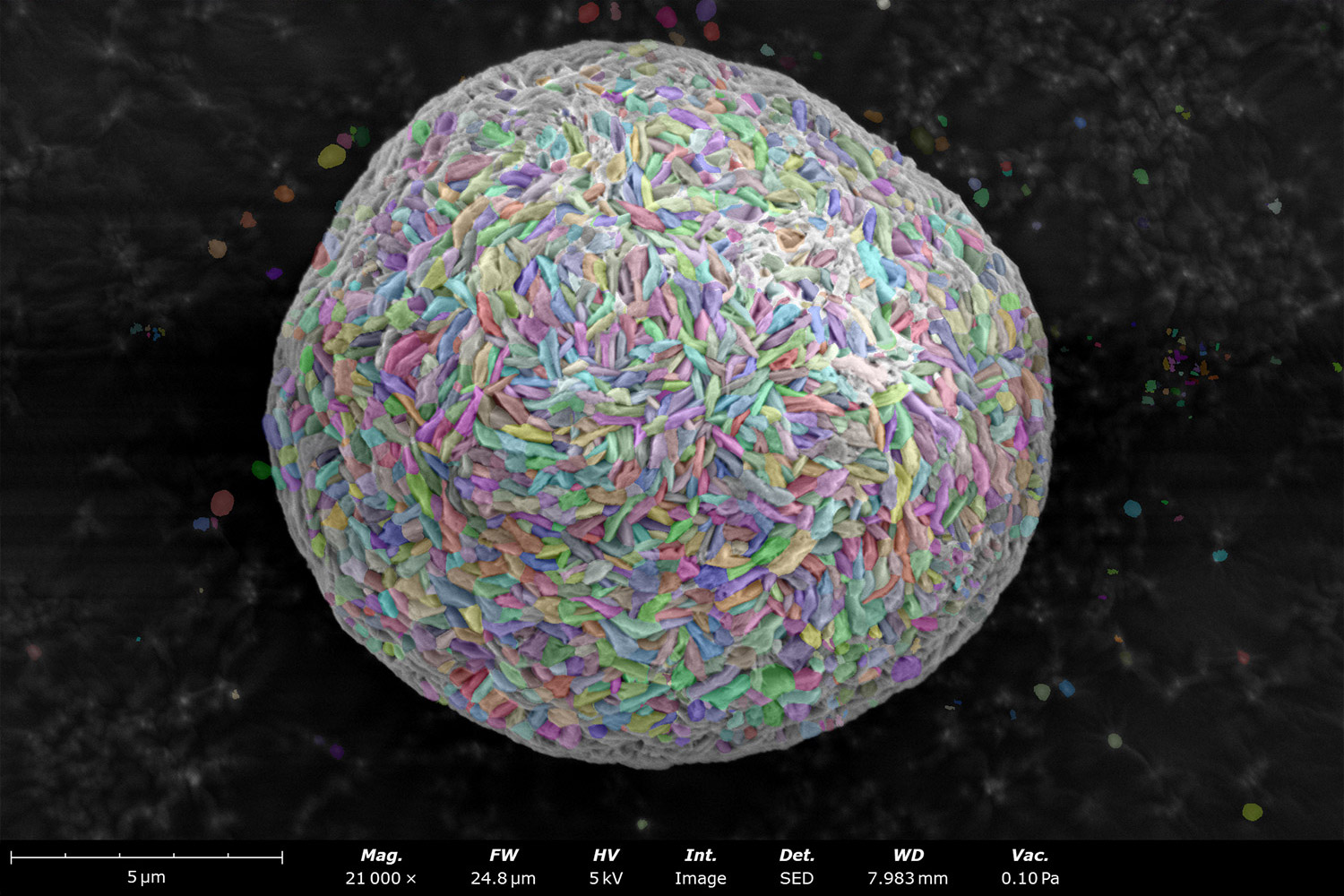

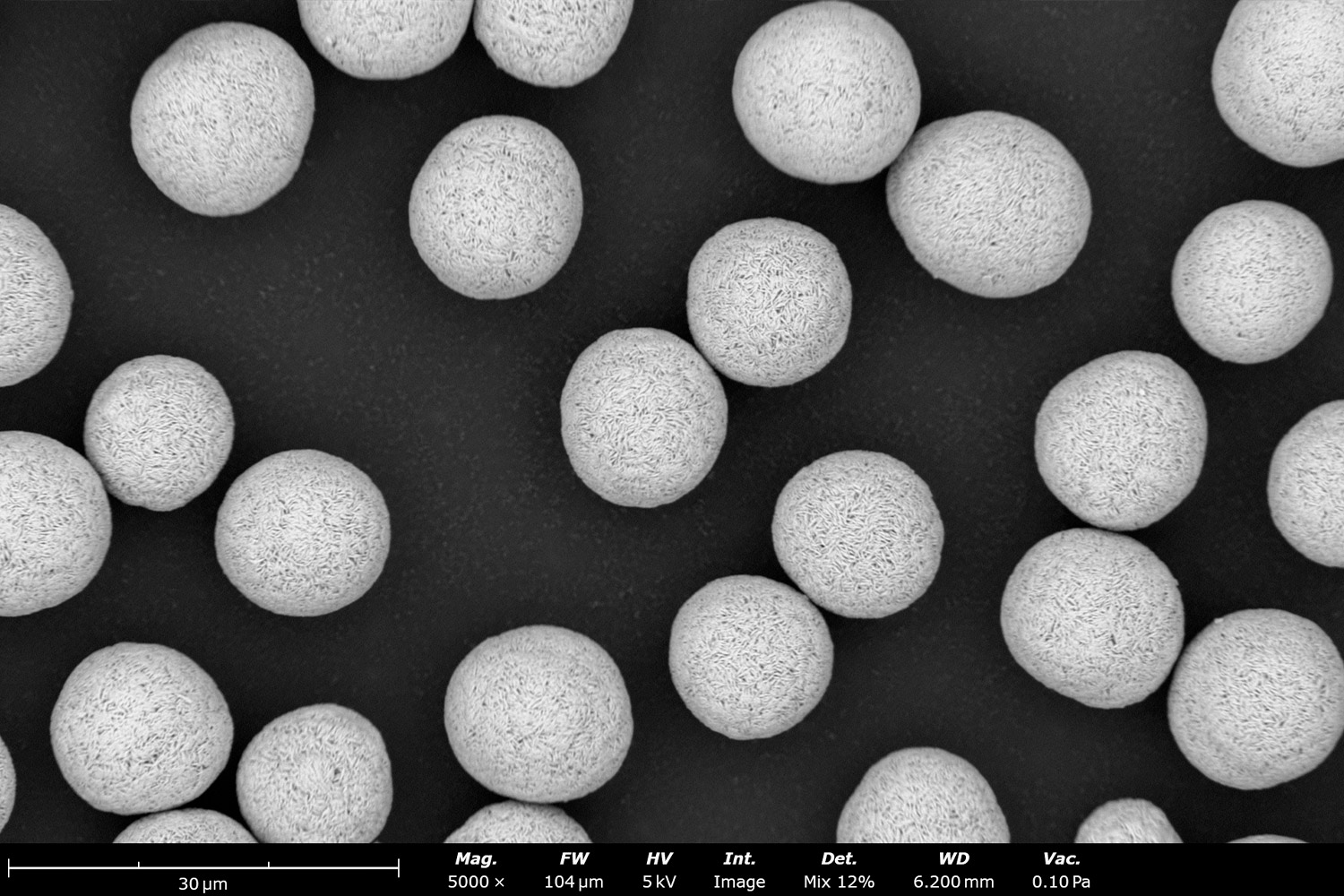

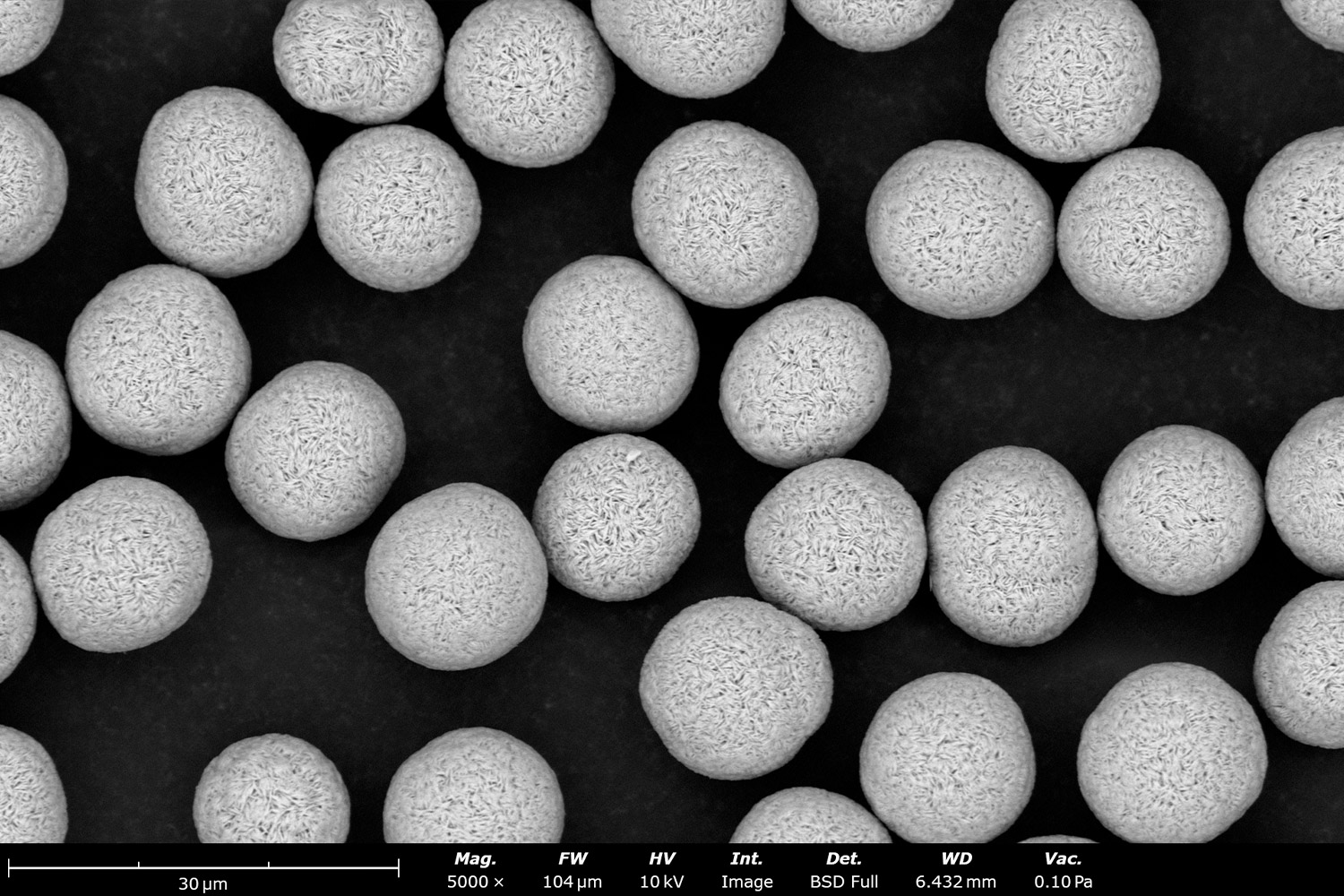

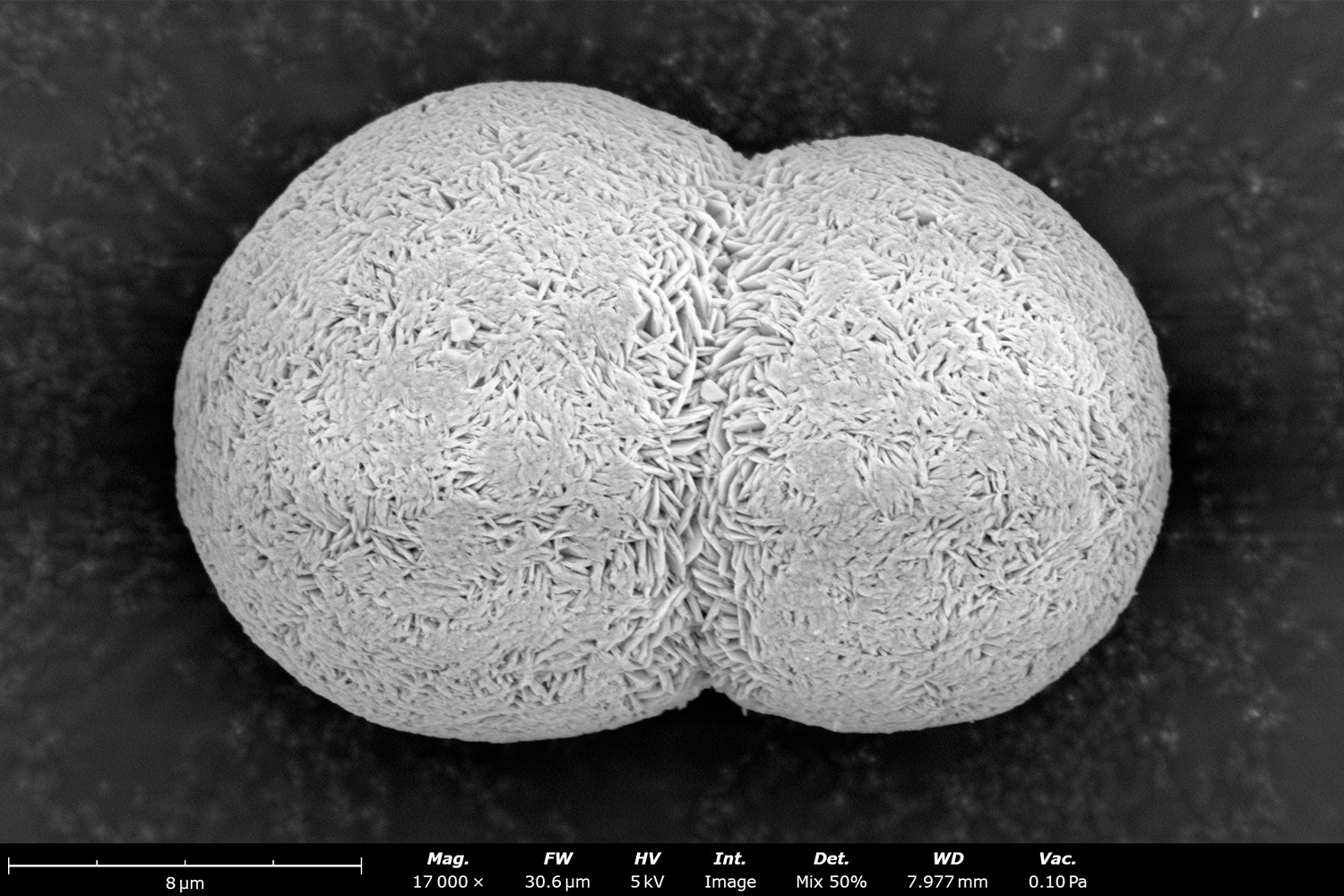

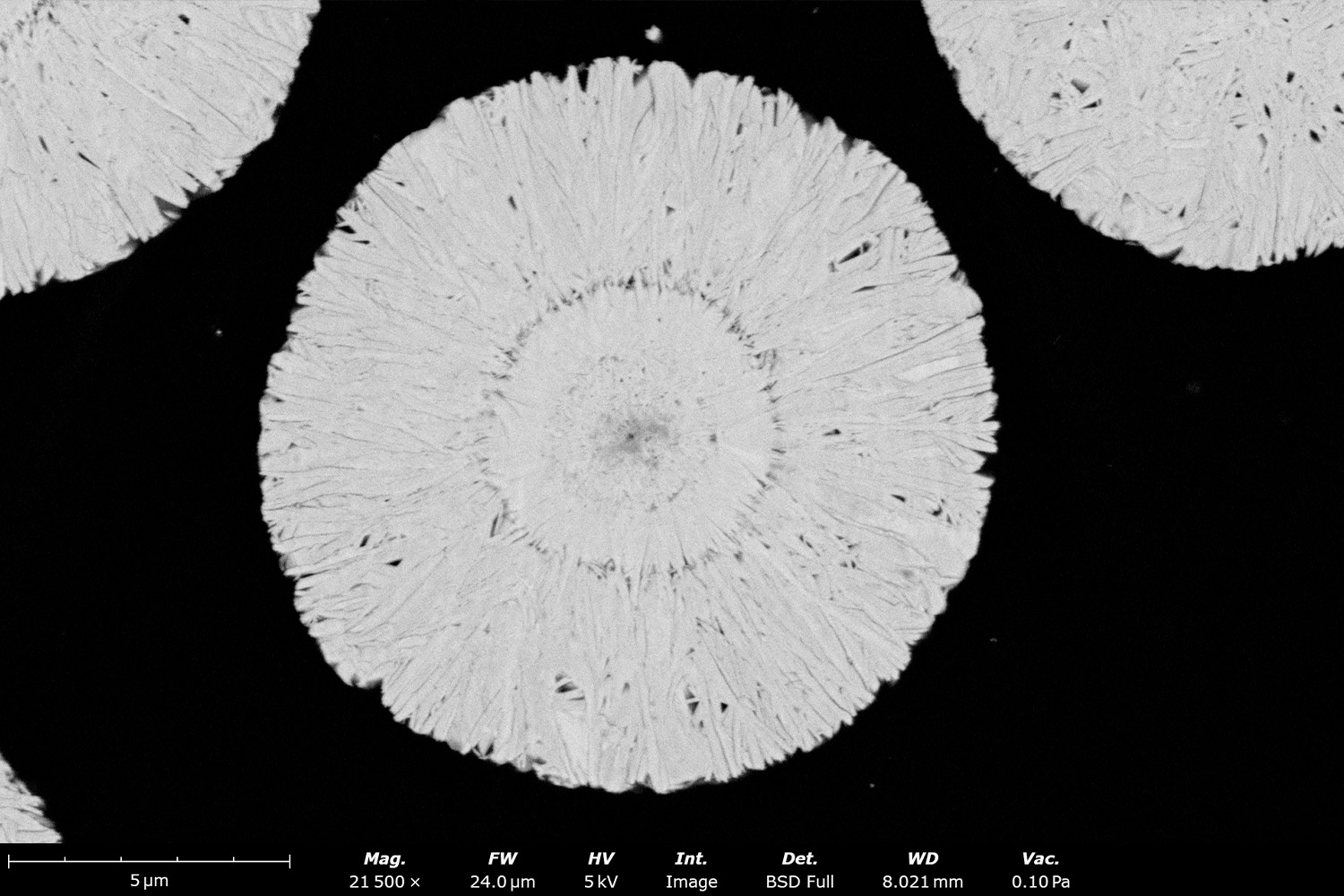

As stated in its name, pCAM is a precursor material for cathode active material (CAM). It is a fine crystalline ceramic powder that serves as an intermediate material for cathode active material (CAM). CAM makes up the bulk of the cathode mass, through which lithium ions intercalate and deintercalate during charging and discharging in lithium-ion batteries. The surface of pCAM particles is comprised of primary particles, which appear as “basket weaves” as seen in Figure 1. pCAM is composed of electrochemically active transition metals such as Nickel (Ni), Manganese (Mn), Cobalt (Co), Iron (Fe), and Aluminum (Al). The most common composition classes of cathodes in lithium-ion batteries are referred to as: NMC (Ni Mn Co), NCA (Ni Co Al), LFP (Li Fe P), LCO (Li Co O), and LMO (Li Mn O). In EV batteries, NMC and LFP are the dominant chemistries, but this article will focus on NMC pCAM.

In industry, NMC pCAM is typically synthesized in continuous stirring tank reactors (CSTR) via coprecipitation reactions. After synthesis, it is typically filtered, washed to remove all the unreacted reagents and coprecipitation by-products, and dried.

pCAM is converted to CAM through a process called lithiation. During this step, lithium, dopants, and particle surface coating materials are dry mixed with pCAM. It is then calcined, washed, dried, and combined with binder, solvent, and carbon black. This final mixture is then coated onto a battery-grade aluminum foil, dried again, calendared, and then cut to size to fabricate the final cathode.

How Does pCAM Quality Impact Battery Development?

Particle Size & Particle Size Distribution

Particle Morphology

Spherical particles have the largest surface contact area per unit volume for lithium ions to travel through compared to other geometries. They also allow for better packing, which increases the volumetric energy storage capacity per battery. Poor sphericity, like the agglomerated particles shown in Figure 3, can lead to poor flowability, which is detrimental for powder transfer and reduces cathode production efficiency. A pCAM particle’s surface area can be influenced by surface porosity, as well as the size and shape of its primary particles. High porosity and small primary particle size can result in a better rate capacity, but can make the particle more susceptible to side reactions and reduce cycle life.2

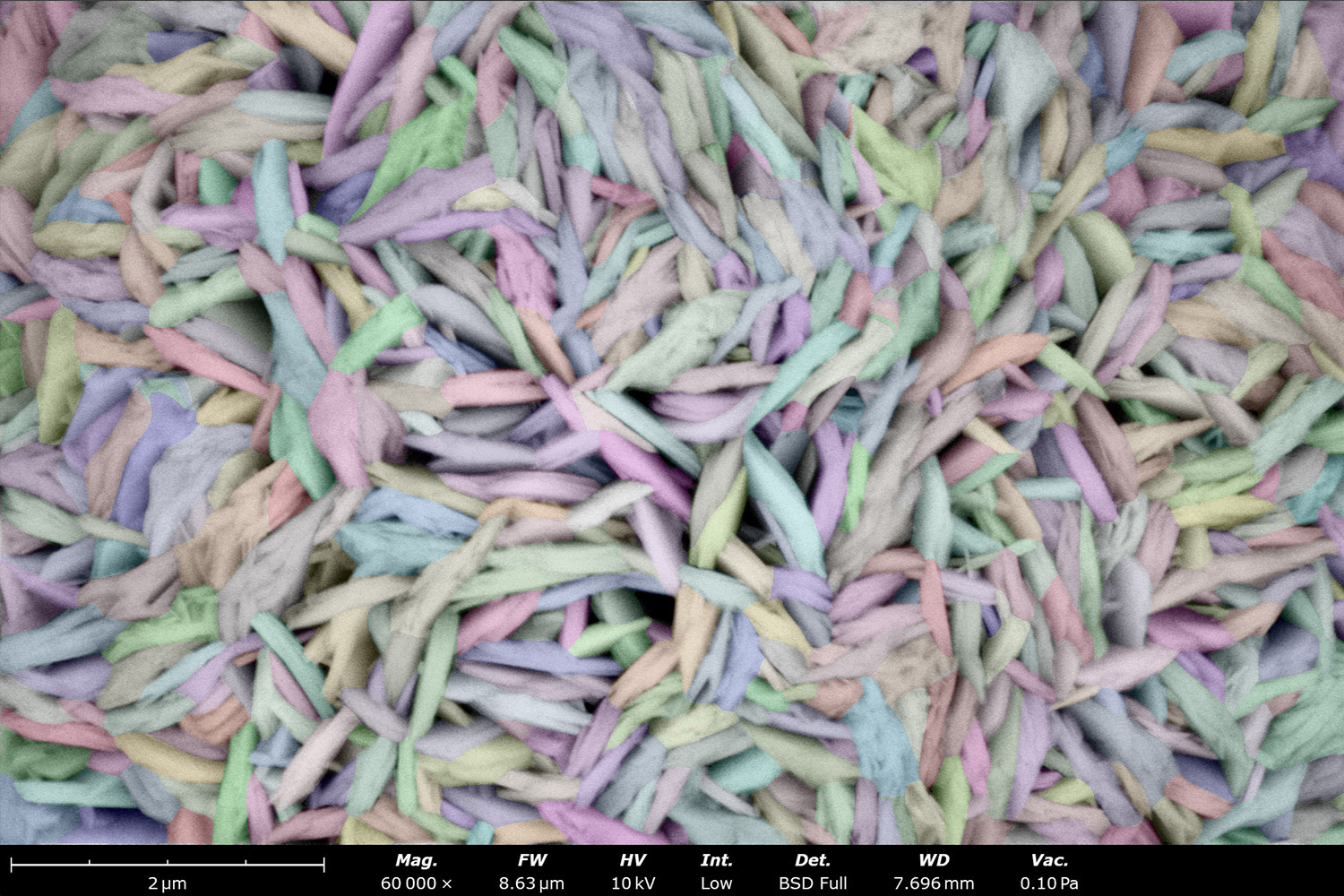

Crystal Microstructure and Orientation

Purity

Which Analysis Techniques Can Characterize pCAM Properties?

CAM quality is directly related to the morphology of its pCAM. This means that imaging the primary and secondary particles within pCAM and tracking them during their growth in a co-precipitation reaction is critical for CAM quality control.

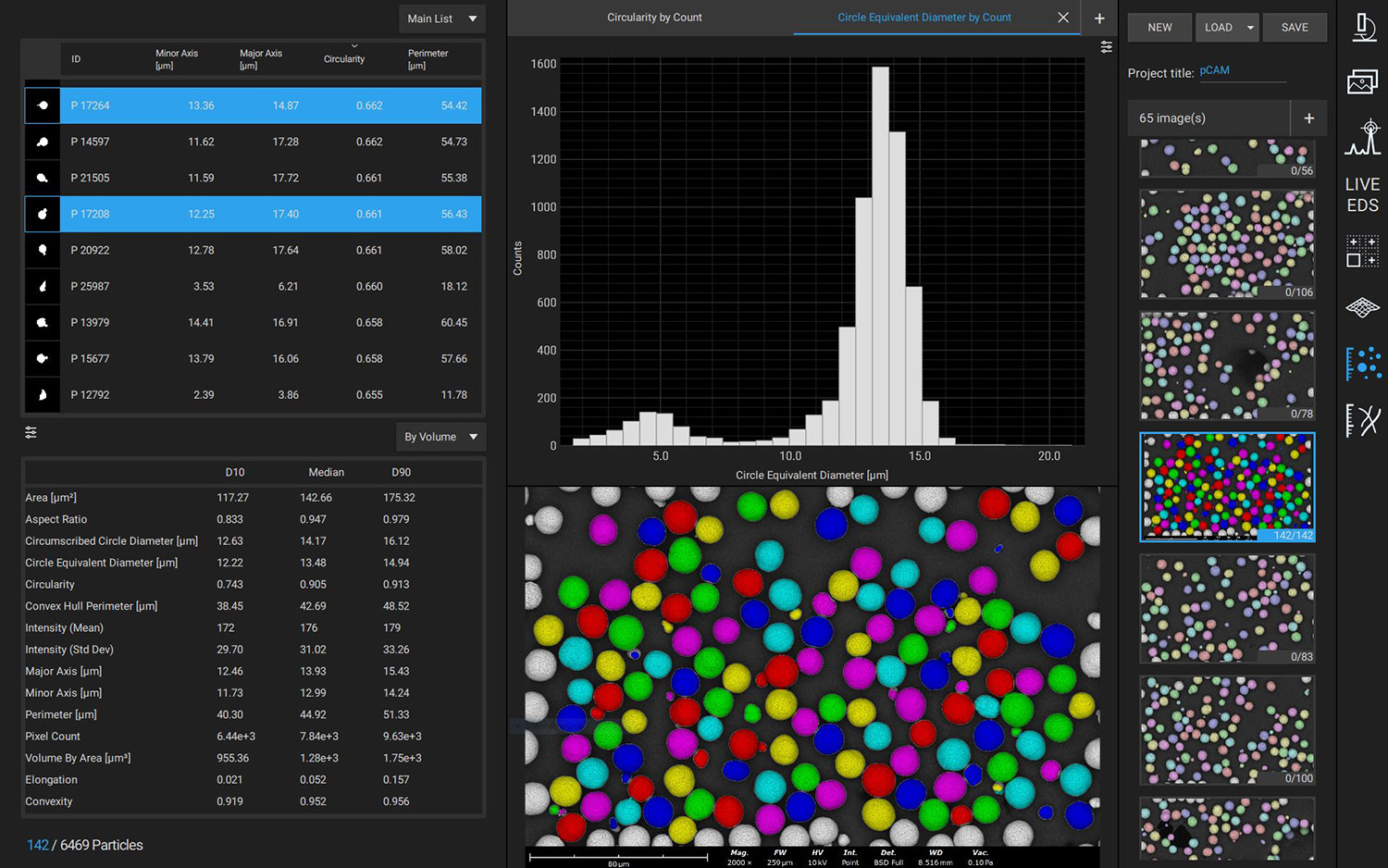

Phenom desktop SEM instruments combine high-resolution imaging with ease-of-use and robustness. They can also be equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), enabling elemental composition analysis alongside morphological analysis. SEM-EDS imaging can also be automated with built-in stitching tools, such as Automated Image Mapping (AIM) and MAPS. Large batches of images can then be automatically analyzed using software tools like ParticleMetric (Figure 5) or Avizo Trueput (Figure 6) to obtain particle size dimensional statistics on particles such as sphericity or particle size distributions, and primary particle thickness.

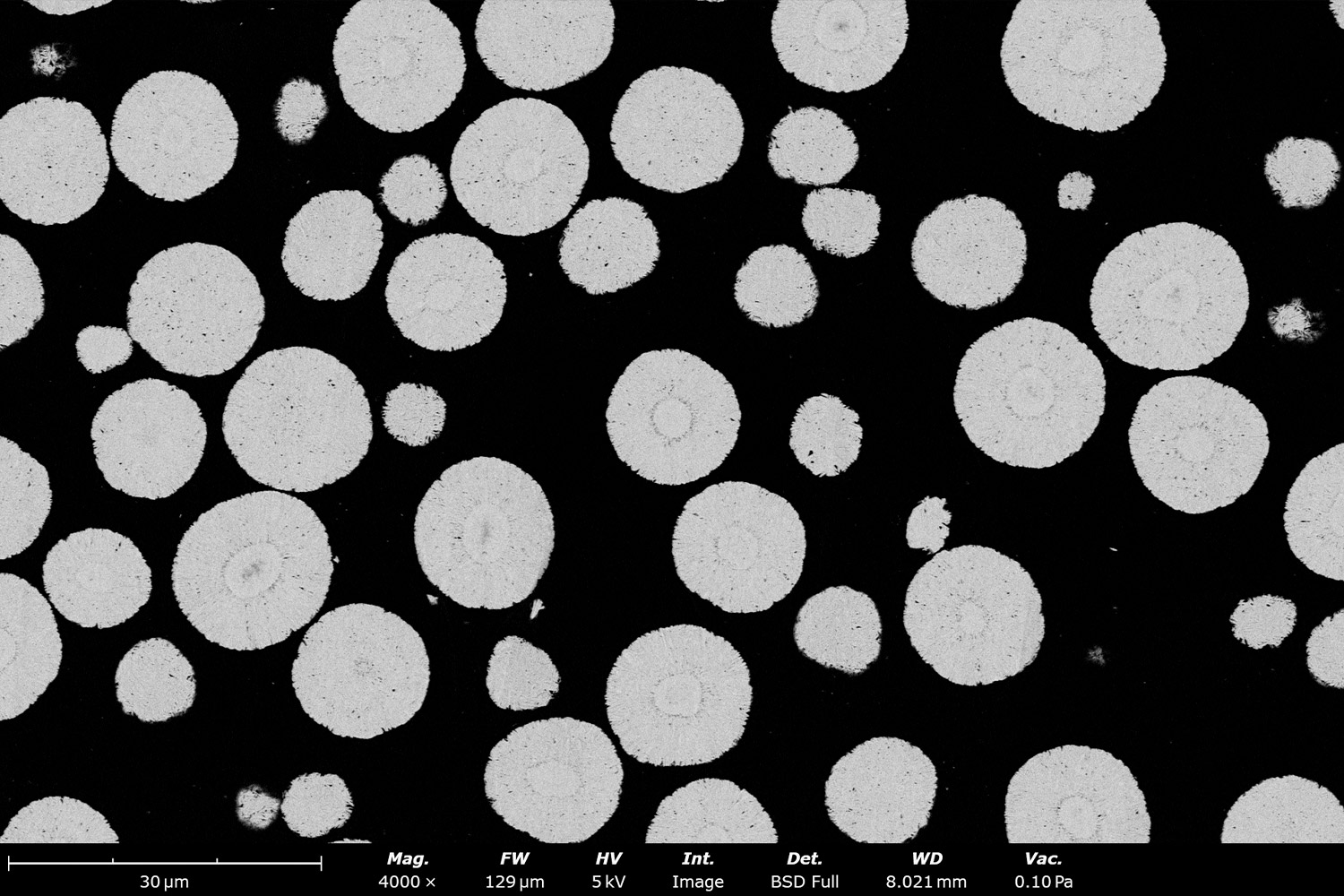

Creating clean cross sections of pCAM particles to analyze the crystal orientation can be extremely difficult with standard preparation methods. However, ion milling, more specifically broad ion beam milling (BIB), can be used to overcome this obstacle. BIB milling is gentler and more precise than typical mechanical polishing technique, while requiring much less effort from the operator.

The SEMPREP SMART is a BIB ion milling system that uses a beam of argon ions to evenly remove material from the surface of a sample. This creates a clean cross section of the sample. While liquid nitrogen or Peltier cooling are required to process some samples, pCAM can be milled with no additional cooling due to the SEMPREP SMART’s sample holder and ion beam designs. After ion milling, the cross sectioned powders can be imaged with SEM to analyze features such as porosity and crystal orientation which were previously hidden beneath the sample surface. Figure 7 highlights the difference that ion milling can make on pCAM SEM imaging.

Software tools like Avizo Trueput can automatically analyze pCAM cross sections for porosity, size distribution, presence of cracks, and more. With this information, battery material engineers and scientists can determine if and how they need to modify their synthesis recipes.

Key Takeaways

- pCAM powders are transition metal compounds that are fundamental to cathodes and their properties. Currently, the two most common pCAM chemistries in EV batteries are NCM and LFP.

- The quality of NMC pCAM powder has a direct impact on the final cathode properties, including volumetric energy density, charge cycle life, and more.

- BIB ion milling, SEM, and automated imaging software are valuable techniques for assessing and optimizing pCAM quality, especially for high throughput in industry.

References

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, J.; Sun, K.; Wang, Z. Balancing particle properties for practical lithium-ion batteries. Particuology 2021, 61, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2021.05.006. ↩︎

- Meng, Z.; Ma, X.; Azhari, L.; Hou, J.; Wang, Y. Morphology controlled performance of ternary layered oxide cathodes. Communications Materials 2023, 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-023-00418-8. ↩︎

- Jamnik, J.; Maier, J. Nanocrystallinity effects in lithium battery materials. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2003, 5 (23), 5215. https://doi.org/10.1039/b309130a. ↩︎

- Zhou, X.; Hong, F.; Wang, S.; Zhao, T.; Peng, J.; Zhang, B.; Fan, W.; Xing, W.; Zuo, M.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Lv, G.; Zhong, Y.; Hua, W.; Xiang, W. Precision engineering of high-performance Ni-rich layered cathodes with radially aligned microstructure through architectural regulation of precursors. eScience 2024, 4 (6), 100276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esci.2024.100276. ↩︎

- Chen, W.; Han, X.; Pan, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Kong, X.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.; Shen, W.; Xiong, R. Defects in lithium-ion batteries: From origins to safety risks. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 2024, 4 (3), 100235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geits.2024.100235. ↩︎